|

| Thelma Johnson Streat graduated form Washington High School in 1932 and became one of the most important artists of her generation. |

Portland’s African-American community has always been

small, but very active and vibrant. In my book Hidden History of Portland (2013) I describe how Portland’s black

community took political action against the discrimination they faced in the

early decades of Portland’s history. Beatrice Morrow Cannady, Portland’s first

black woman attorney, led the fight for civil rights and dignity from

1912-1936. One of her most radical and effective organizing tools was a series

of inter-racial Tea Parties designed to highlight the cultural achievements of

black Americans and give white Portlanders the opportunity to get to know their

black neighbors. In September, 1934 Cannady highlighted the achievements of a

young Portland artist named Thelma Johnson, who under her married name (Thelma

Johnson Streat) would become one of the most celebrated artists and educators

in the country.

Born in 1911 in Yakima, WA Thelma began to paint when she

was seven and moved to Portland with her family where she graduated from

Washington High School in 1932. She

gained her first national recognition in 1929 when her painting, A Priest, received honorable mention at

the Harmon Exhibition in New York. She studied at the Museum Art School (now

the Pacific Northwest College of Art) and in 1934 the Portland Advocate, edited by Beatrice Cannady, sponsored her first

exhibition at the YWCA. In 1938 she exhibited a “one-woman” show at the J.K.

Gill Art Gallery. Shortly after the Gill Gallery show, Thelma married Romaine

Streat and moved to San Francisco where she took a job with the Arts Project of

the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

In San Francisco Streat worked with Diego Rivera, the

renowned Mexican painter, on his Pan-American Unity mural and began to receive serious

recognition. Rivera said that her work was “one of the most interesting manifestations

in this country at the present. It is extremely evolved and sophisticated

enough to reconquer the grace and purity of African and American art.” While

working at the famed Pickle Factory art studio in 1941 Streat completed her

most famous painting, Rabbit Man. The

next year Rabbit Man was acquired by

New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and Streat became the first African

American artist to be exhibited in MoMA’s “New Acquisitions” show.

In 1943 Streat moved to Chicago where she exhibited

paintings and studied at the Art Institute creating her most controversial

painting, Death of a Black Sailor. The

painting, done in mural style, depicted the death of a black sailor who risked

his life in the war to defend democratic rights he was denied at home and

earned Streat death threats from members of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). Inspired by the thought of Beatrice Cannady,

who believed that education was the key to attaining civil rights, and spurred

on by the threats from the KKK, Streat initiated a visual education program

called “The Negro in History.” As part of that program she painted portraits of

Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson and Harriet Tubman among others.

In 1945 Streat returned to Portland and although she

traveled extensively she always returned home to Portland where she exhibited

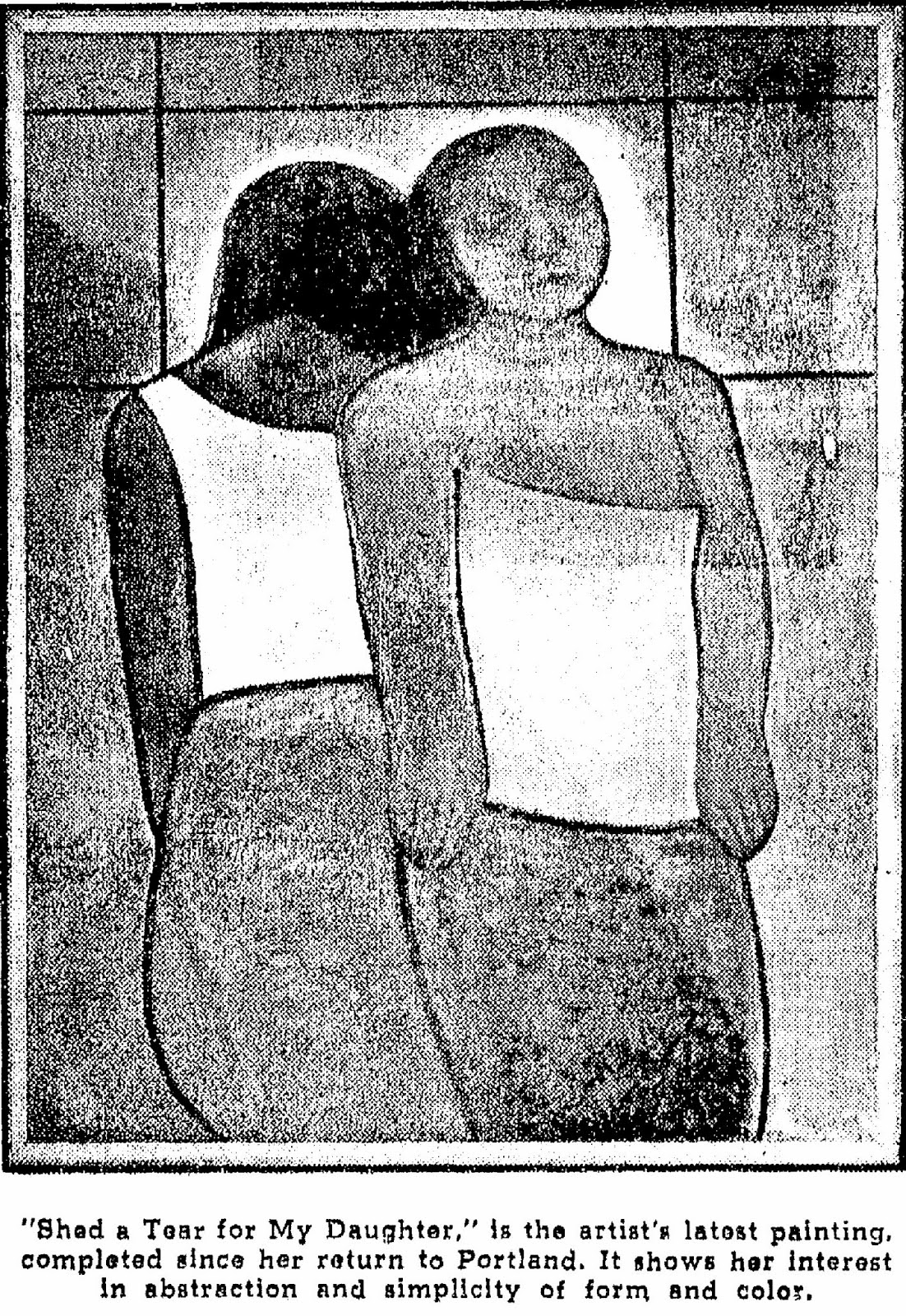

paintings and performed dance. In Portland Streat painted another celebrated

painting, Shed a Tear for My Daughter,

and began the next stage of her career as an expressive dancer. Before coming

home to Portland she had spent time in Queen Charlotte’s Island where she

studied dance and painting with the Haida people. She incorporated the bold

colors and strong graphic design of Haida art into her own work and studied

their traditional dance. In August 1945, at a home in Northeast Portland,

Streat presented a dance performance in front of one of her paintings. Streat

danced an expressive dance influenced by Haida performance and the principles

of abstract art, with narration provided by her sister’s poem “The Negro Speaks

of Faith.”

Thelma Streat’s dance performances were very popular and

she made dance and music a focus of her work for the rest of her life. In 1948

she married Edgar Kline, a playwright and producer who had been her manager for

three years, and expanded her career internationally. She and her second

husband traveled the world exhibiting her paintings and performing dance,

before settling in Honolulu in 1950, where she founded Children’s City, an

education center that taught art as well as tolerance through the appreciation

of cultural diversity. “If I can any small way nourish the minds of island

children, if I can enlarge their horizons, then the purpose of my work is

fulfilled,” Streat said, “The principal aim of Children’s City is to eliminate

those prejudices which are the outgrowth of misinformation concerning peoples

of different ethnic, economic, and cultural backgrounds….”

Thelma Johnson Streat broke many barriers and received

many honors in her life. She was the first African-American woman to have a

painting exhibited at MoMA and by 1947 she was one of only four

African-American abstract painters to have had solo exhibitions in New York. In

1949 she became the first American woman to have her own television program in

Paris and in 1950 she performed a dance recital at Buckingham Palace for the

King and Queen of England. She was also a frequent visitor in the home of Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1958 Streat began making plans for a second

Children’s City that she planned to open in Saltspring Island, British

Columbia. She never got to open the second school, because she died suddenly in

Los Angeles, where she had begun to study anthropology at UCLA, in 1959. Streat’s

importance has only increased since her death.

She continues to have exhibits of her work and in 2010 she was awarded a

posthumous doctorate from the Pacific Northwest College of Art. Her painting Black Virgin is in the collection of

Reed College.

If you enjoyed this post and think the work I do is worthwhile I hope you will support my campaign on Patreon.com. Please follow the link and make a pledge. It is very important.

No comments:

Post a Comment